From the Gold Standard to Bretton Woods: Shifts in International Monetary Policies of the United States¶

by MB, JC, KC Group Metadata Mavens

Data Overview, Telling Our Story¶

Historical Context In the 1930s, as economies around the globe foundered, the United States responded with several important new monetary policies. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6102 (1933) placing limits on the amount of gold which could be held by individual Americans and ordered that gold be surrendered to the U.S. Treasury in exchange for cash. The U.S. suspended the gold standard and the Treasury under Henry Morgenthau, Jr. issued more currency to stimulate the national economy. Those actions, however, resulted in an exchange imbalance between the U.S., Great Britain, and France. Beginning in 1936, the U.S. developed an informal international partnership called the Tripartite Agreement to stabilize currency and exchange rates among the three. Soon after, additional gold-bloc European nations joined as what Morgenthau termed “junior members” (Morgenthau, 1938, May 9). The international monetary policy development culminated near the end of WWII with the Bretton Woods Conference of 44 Allied nations assembled in New Hampshire to agree on a new international monetary system. (MB)

Data Selection & Question Of the two series of the Morgenthau Press Conferences, our focus was Series 1, which is a set of index cards alphabetized by subject, pointing one to the full-text transcripts in Series 2. Each card contains a subject heading, date(s), volume number, and page numbers which refer to the corresponding collection of press conference transcripts, and a summary or summaries of key points arranged in outline form. In some cases, the cards include a number indicating that it is one in a series of related cards. Occasionally, cards cross-reference other subject headings. (JC, MB)

Looking through the subject headings of the index cards, our team was drawn to the heading ‘Silver.’ Recognizing silver as an important aspect of U.S. economics during and leading up to the FDR Administration, we wanted to identify patterns and gaps in their content and use it as a starting point for transcription. Reading through the cards, our group then noted frequent references to ‘Stabilization,’ and so expanded our data set to include cards with that subject heading as well. Supplementing the cards with external historical context, we recognized gold to be of a more central focus to stabilization efforts than silver, and recalibrated our efforts in the cards accordingly, to those filed under the subject headings ‘Gold’ and ‘Stabilization.’ Transcription of those cards led us to detect another pattern, and we expanded the set again to include data with another subject heading that was a frequently referenced term within both the ‘Gold’ and ‘Stabilization’ cards: ‘Tripartite Agreement.’ Those word patterns formed the nucleus of our approach, and our driving question: How do the subjects relate to each other and how could a dataset developed from them potentially benefit historical research? Our aim in answering this question was to identify and pull out notable keywords that appear in the card summaries, mapping them along a timeline to show their frequency of appearance. With this timeline in place, users can visually track how international monetary stabilization efforts developed across a historical trajectory, considering trends and gaps in what Morgenthau shared with the press.

Dataset Exploration related to Scale and Levels within Collection¶

The Morgenthau Press Conference Collection consists of qualitative data, both nominal (subject headings, names, references) and ordinal (dates). The collection comprises two series. Within Series 1 the subset chosen for this work (cards filed under the subject headings ‘Gold,’ ‘Stabilization,’ and ‘Tripartite Agreement’) totals 199 index cards. Data exploration concentrated on subject headings and subject tags derived from the summary text of each card. Dates and geographic information were also considered. Volume numbers and page numbers were transcribed and entered into the spreadsheet, but not used in computation, as they were outside the scope of our project focus on subject summaries and their corresponding dates. (MB, KC)

Data Cleaning and Preparation¶

We transcribed 199 cards filed under the subject headings ‘Gold,’ ‘Stabilization,’ and ‘Tripartite Agreement’ in their entirety into a Google Sheets spreadsheet, tagging each entry with a keyword in the ‘summary_id’ column. (JC, MB)

3A. Transcription

As a team, we elected to divide the cards and the responsibility for transcribing the data from them into a shared Google Sheets spreadsheet in accordance with agreed-upon schema. The schema included column headers for Source, PDF Page Number, Card Number, Subject Heading (SH), SH Serial Number, Volume Number, Conference Meeting (CM) Summary, CM Date, CM Book Number, and CM Pages. We also included a column labeled “Transcription Notes,” where we could note discrepancies and changes we made from the original text (such as changing Roman numerals to Arabic, and the decision to spell out abbreviations). (MB, JC)

Each team member was responsible for choosing a method of transcription: two did so manually, entering the data directly in the spreadsheet; the third used Adobe PhotoShop and a batch processing script. The workflow for the batch processing began with importing the multipage PDF into Photoshop and selecting the appropriate page range for our data set. The import command was then set to open all selected pages as individual images, in grayscale, at a 1000 pixel/inch resolution. A batch script cropped every open file to a custom frame, applied a brightening filter with a setting of +75, and saved the edited files in a preselected folder. This process reduced image size by removing the extraneous black frame (albeit imperfectly as the PDFs were not uniform), whitened the background, and improved contrast between background and text. Using a batch script meant dozens of pages could be processed in minutes. The individual PDF files were then reassembled into binders of about 10 pages, and uploaded to OCRspace using OCR Engine 5. See Figure 1 for the comparative accuracy achieved regarding (Morgenthau 1944).

In the first attempts, the OCR’d results were output as JSON snippets, converted to CSV files at convertcsv.com, and then imported into Google Sheets. Unfortunately, the cards’ formatting resulted in CSV files with a nonsensical arrangement which could not be overcome efficiently using either the spreadsheet or OpenRefine. The process was repeated, outputting the OCR’d results to plain text, manually edited, and pasted directly into the spreadsheet. Still awkward and unwieldy, this method nevertheless provided faster, better results than when using JSON. (MB)

3B. Data Worksheet

Transcribing the text-based informational content recorded on the index cards into a spreadsheet format led our group to consider how best to organize and break-up that data. Each group member had a different perspective, resulting in critical conversations about the overarching effects of transforming static text into fluid data.

The summaries on the cards take several forms. Some cards present a single summary line with corresponding date and reference to where the information appears in the bound volumes of press conference transcriptions (see for example page 158 of the PDF file mp06, earlier cited as Morgenthau 1944). Other cards include multiple summaries from separate dates, referenced in different press conferences (see pages 141-2 of Morgenthau 1944). Sometimes summaries span multiple cards (same). Other cards provide summaries that are broken into one or multiple subpoints (see page 143 of Morgenthau 1944). We debated whether to keep content together based on the card on which it appears, or—as in the case of entries that span multiple cards—to keep information together based instead on summary. We also considered whether to keep multi-faceted summaries clustered in a single row, or to break those subpoints into their own rows, especially if the subpoints were different facets of the larger topic, each concentrating on a unique point that could be keyworded in a different way. Our aim was to group and organize the information in a way that is accurate, neither minimizing nor over-inflating the number of instances that a topic appears in the cards. Ultimately, we decided to group content by summary rather than by card, and to likewise keep multipart summaries together unless they had different dates and transcript locations.

The above step in the process was essentially a negotiation and exploration of the “big bucket” records approach, and, thus, an exercise in non-hierarchical data structure. Whereas traditional computing systems rely upon a hierarchical directory structure to store and retrieve data—one made obvious to human users who interact with that data—modern computing systems now override the need for subdirectories and knowledge of file location in order to retrieve data (Chin 2021). Instead, content can be stored in “one bucket,” and the user need only type a query into a search in order to retrieve the files and applications they seek (Chin 2021, para. 8). In our exploration of the Morgenthau press conferences, we asked ourselves: Do we compartmentalize the data, or combine in a single cell? Do we strive to convey the original, static representation of the information (exactly as it is presented on the cards), or do we free that data, using tools that allow for dynamic reformulating and transformation of that data into something new? In the end, our purpose (creating a timeline that notes frequency of key terms alongside the years of their mention dates of related historical events), and the visualization software we chose to work with (Google Data Studio), informed our decision to keep single and multi-point summaries together if they retained the same date and represented a single key summary point. However, other researchers might take a different approach, depending on their end goals and the requirements or limitations of the software they use to manipulate and visualize the data. (JC)

Once the transcribed data from each team member was appropriately assembled as a set in a spreadsheet, we normalized the data, making modifications intended to make the data more useful. Dates and page numbers were converted to a standardized format. Roman numerals were converted to Arabic. Cards referencing multiple subjects or press conferences on different dates were split into multiple line entries. A column (summary_id) was added so each entry could be tagged with a categorization keyword selected by our group for highlighting. Figure 2 provides a list of the keywords we developed. (MB)

Figure 2: Summary_ID Keywords Shown in OpenRefine.

OpenRefine was used to isolate and correct misspellings, cluster and edit records, standardize date formats, and consolidate and refine categorization. The second pass of the data using OpenRefine reduced the number of discrete tags from more than seventy to just over fifty. After the second pass through OpenRefine, the team elected to add another column to the Google Sheets spreadsheet and move or add geographical tags there in order to facilitate geospatial visualizations in the future. (MB)

Modeling: Computation and Transformation¶

To explore patterns in the data we decided to track topic mentions and their count over the timeline presented by the cards. As a software tool, Google Data Studio allows for such manipulations, is free, and includes the option for visualizations. It also allows for data upload by linking straight to Google Sheets which is where we consolidated our transcriptions and formed a small database. Google Data Studio is not faultless: it has a chart feature that operates through SQL statements, but does not let you see those statements. Also, to be able to input your own SQL statements there is a fee. If our project were larger in scale we would recommend looking elsewhere, but Google Data Studio fit our needs and, with knowledge of basic SQL, it is possible to track what statements Google Data Studio employs. To look for patterns in our data set, Google Data Studio performed the following SQL statement: (KC)

- SELECT summary_id_new,

- COUNT (*)

- WHERE summary_id_new IS NOT NULL

- FROM Full_Data_Set_Cleaned

- GROUP BY summary_id_new, date

- DATE_TRUNC (‘year’, date)

- HAVING COUNT (*)

Modeling: Visualization¶

Aldhizer (2017 p. 30) speaks on the importance of visualizations in auditing and accounting, noting that “visual analytic software may more easily uncover otherwise hidden relationships between data elements.” Rose et al. (2022 p. 71) find in their experiment that “different visualizations of the same audit evidence can yield different levels of cognitive and emotional arousal. Prior psychology research finds that arousal levels are important determinants of attention, cognitive processing, and memory encoding.” Though both resources focus on auditors and accountants, both findings can be applied to areas or people (users) in the humanities as well and are applicable to our examination of Morgenthau’s press conference summary cards. (KC)

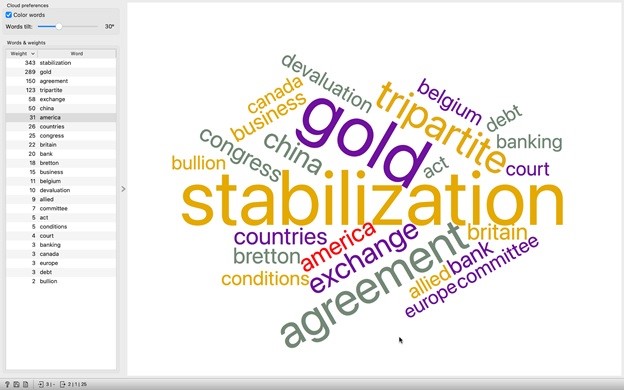

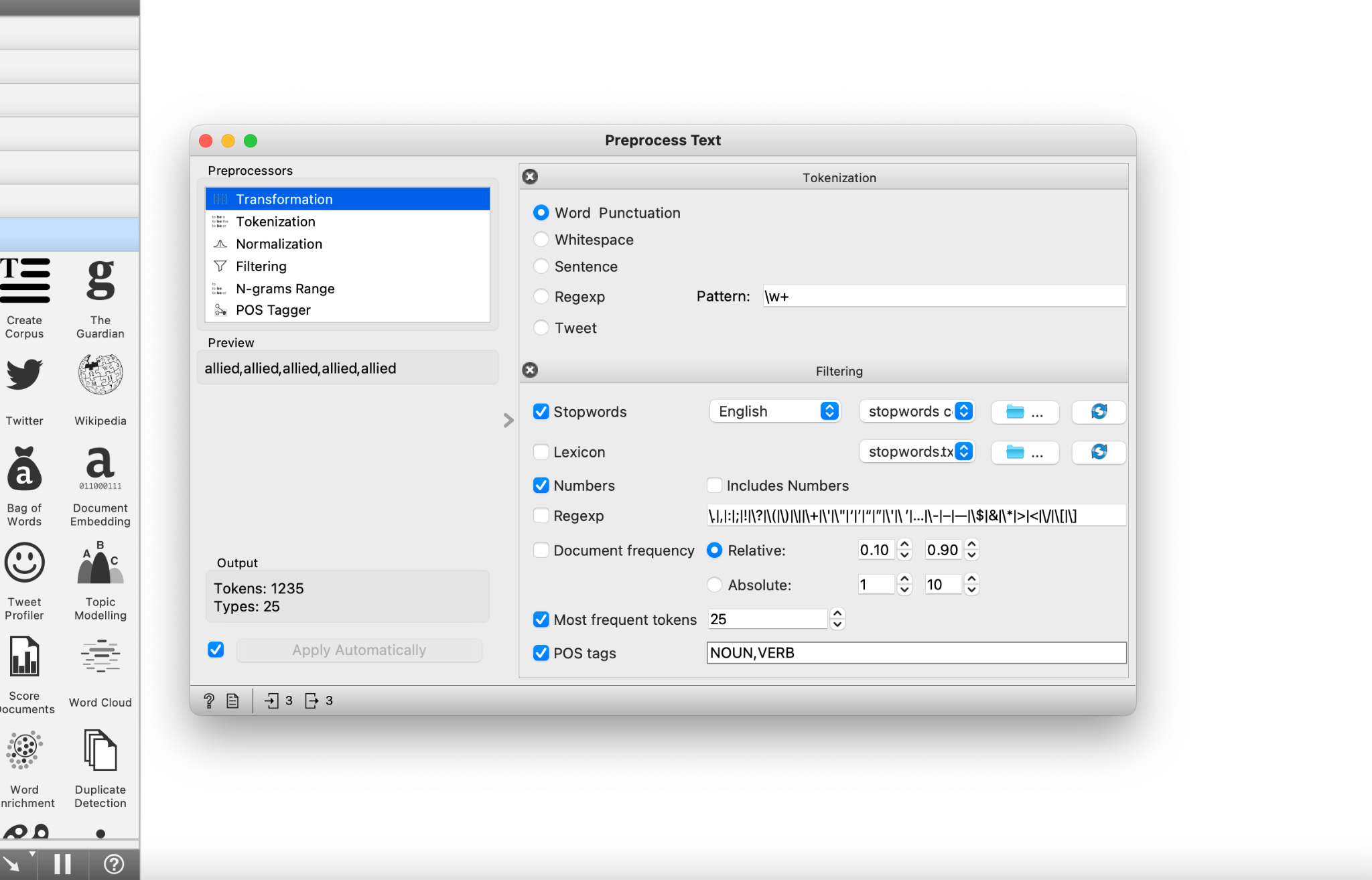

A simple word cloud created in Orange Data Mining visually highlights key topics from the cards’ data. The text from worksheet columns “subject_heading” and “summary_id_new” was imported into Orange Data Mining. Each column was treated as a separate document in the corpus builder to achieve the appropriate frequency weight for repeated terms. The assembled text was tokenized to remove punctuation, then filtered to remove numbers and stop words using a standard list and another created for these documents. The custom list included Morgenthau’s initials and forms of punctuation not addressed by tokenization. Terms were treated in relative frequency to documents and output was limited to NOUNS and VERBS. The resulting word cloud is shown together with a list of the weighted terms in Figure 3. The workflows are shared as Figures 4, 5, and 6. (MB)

Figure 3: Topic Word Cloud. Note: The word cloud shows the 25 most frequently occurring unique terms within the “summary_id,” “summary,” and “subject_heading” fields and the weighted value of each word is shown in the table on the left.

Figure 4: Word Cloud Workflow. Note: Text was imported into the widget as three documents, compiled into a single corpus, preprocessed, and output to a Word Cloud.

Figure 5: Create Corpus Widget Dialog. Note: Each column imported from the spreadsheet was treated as a separate document to give terms the appropriate weighting.

Figure 6: Preprocess Text Widget Dialog. Note. The data corpus was transformed and filtered; the text did not require stemming or normalization.

After much deliberation, it was decided that the best way to represent the data trends over time was with a visualization made using the SQL manipulation within Google Data Studio. The resulting time series chart is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Visualization using Google Data Studio. Note: Chart shows topics present in the Gold, Silver, Stabilization, and Tripartite Agreement index cards and their count by year.

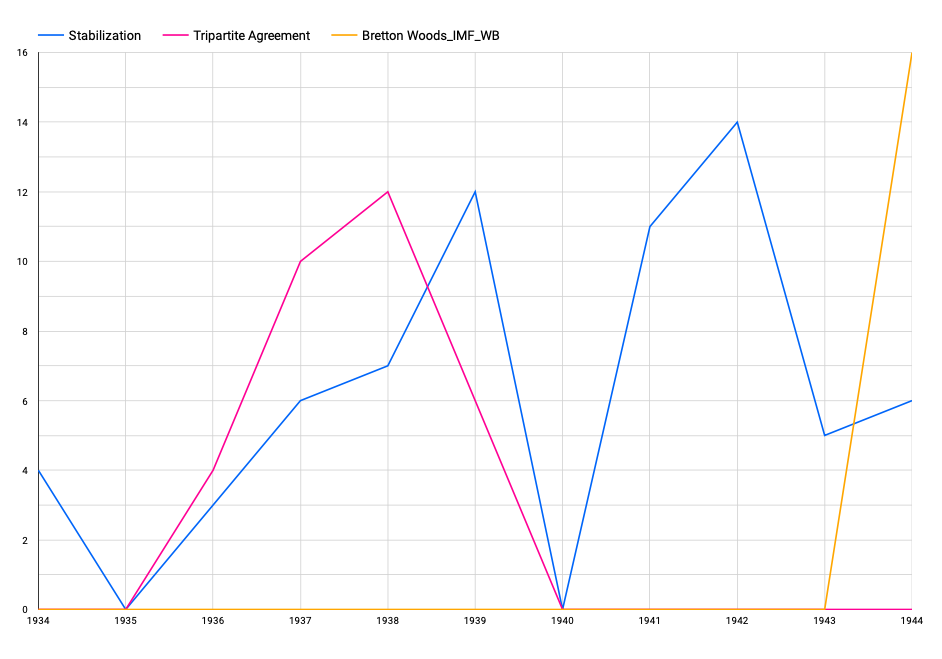

Our primary points of interest shown within Figure 7 are the sudden rise and fall of the Tripartite Agreement (pink) from 1935-1940, the thread of Stabilization (blue), and the meteoric rise of Bretton Woods_International Monetary Fund_World Bank (orange) in 1944. To more clearly showcase these primary points of interest visually, we isolated these topics with the following SQL query, the results of which are shown in Figure 8: (KC)

- SELECT summary_id_new,

- COUNT (*)

- WHERE summary_id_new = ‘Tripartite Agreement’ OR summary_id_new = ‘Stabilization’ OR summary_id_new = ‘Bretton Woods_IMF_WB

- FROM Full_Data_Set_Cleaned

- GROUP BY summary_id_new, date

- DATE_TRUNC (‘year’, date)

- HAVING COUNT (*)

Figure 8: Second Visualization using Google Data Studio. Note: Isolation of the terms Stabilization, Tripartite Agreement, and Bretton Woods_IMF_WB.

Layering this visualization of the terms “Stabilization,” “Tripartite Agreement,” and “Bretton Woods_IMF_WB” against major historical events during WWII relays important context underlying the cards. (JC) On September 1, 1939, the war began in Europe with the German invasion of Poland. By June of the following year, German forces occupied Paris and much of London lay in ruins from constant air bombardment. With the United States’ European partner nations engaged in war, the tripartite agreement was effectively ended. In December, 1941, the United States declared war on Japan and Germany and domestic manufacturing capabilities shifted to military production under the War Powers Act of 1941. The U.S.’ economic power grew: “By 1945, the United States was manufacturing more than half of the produced goods in the world. US exports made up more than one-third of the total global exports, and the United States held roughly two-thirds of the available gold reserves. The sudden onset of this new position of economic power presented the United States with a number of new [global] responsibilities” (Burton, 2022).

As the war drew to a close in 1944, the Treasury and foreign partners looked to the future, the necessity of rebuilding, and the hope that a new international monetary system would promote economic growth and stability and foster peace (IMF, 2022). In mid-1944, Morgenthau chaired the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire where more than 700 delegates from around the world met to charter the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) (World Bank, 2022). Accordingly, the index cards shifted from the use of the terms ‘Tripartite Agreement’ in the second half of the 1930s to ‘International Stabilization Fund, ‘International Monetary System,’ and ‘World Bank’ in the early 1940s. As noted previously, in our charts the trajectory from the tripartite agreement to the new monetary system is demonstrated in the disappearance of the ‘Tripartite Agreement’ and reappearance of the graph line for ‘Stabilization’ in 1940 and the new graph line for ‘Bretton Woods_IMF_WB’ near the end of the timeline. (MB)

Ethics and Values Considerations¶

A key ethical consideration in this project is recognizing the many layers of information involved, all of which have the potential to skew interpretation of the data, even as accuracy is a primary goal across all project layers. As Donaldson and Conway (2015 p. 2437) note, “the closer the document is to the original or the actual event, the less likely the error or the less likely important information has been omitted, changed or otherwise altered.” One layer with the Morgenthau Press Conference collection is that the original typed transcriptions are primary documents, serving as contemporaneous artifacts of meetings between Henry Morgenthau, Jr. and the press, and prepared by U.S. Treasury Staff. While the transcriptions are both accurate and authentic, they are nevertheless two levels removed from the live events as they occurred: the spoken words were first recorded in shorthand, and then later typed into longhand. While we have no evidence to suggest the transcripts lack accuracy, it is nevertheless possible that the original transcriptions might not capture every nuance, every non-verbal expression that occurred during the live conferences; mistakes, misrepresentations, and misinterpretations are also more likely to occur with each transformation of the original into a new format.

Another layer is that Morgenthau’s staff summarized the conference meeting transcripts onto index cards during his tenure, where words and phrases are sometimes quoted, but more often truncated, and an interpretation of the words generated, even as, again, they are considered primary documents – serving as both accurate and authentic ‘finding aids,’ contemporaneous with the original occurrence of events. Further, the transcriptions and cards were captured onto microfilm in the 1940s under the direction of the U.S. Treasury library, and in 2014, the FDR Presidential Library then digitized the microfilm for public access, translating the original content into new formats.

Our group then imposed additional layers onto the dataset for our project purposes. For data mining, we focused on the index cards only, rather than on the full text of the conference meeting transcripts. The index cards provide detailed summaries of the press conference meetings, with dates, names of people and places referenced, and key phrases shared, including those that were to remain “off the record.” From here, we further summarized the content of the cards, by shortening the card summary to a key phrase in a “summary_id” column, and—where applicable—a geographic location in a “place_id” column. For instance, in Series 1: Index, Silver (cont.)-Tax: Legislation, page 124 of the PDF file mp06 (Morgenthau 1944), the second entry on this card (related to the subject heading “Stabilization”) reads: “Treasury negotiating with Mexico on stabilization loan.” As stated in above section 3B, for data visualization purposes our group reduced that summary down to the single word “Stabilization” in the “summary_id” column, and the single place name “Mexico” in the “place_id” column. Our goal was to pinpoint specific concepts that data manipulation software could easily graph, in order to visually represent patterns noted in the data. Even so, we recognize that with each iteration of the data, the potential for misinterpretation and misrepresentation is possible.

While the visualizations are meant to offer new ways for users to engage with and discover meaning in the data, it is also important to understand that our project is very much an interpretation in itself. Examination of the primary sources to which they refer alongside our results is recommended, while also keeping in mind that implicit bias may be present in each and every layer of the data, from the initial press conferences, transcripts, and summaries, all the way to digitization, transcription, and the summaries our group imposed on the cards as well. (JC)

Summary and Suggestions¶

Working with index card summaries of the Morgenthau Press Conferences—which are publicly available online through the FDR Library—we discerned that the cards trace the trajectory of the U.S. Treasury’s role in economic recovery around the world. They offer an important window into the evolution of the U.S.-led international monetary policy from its nascence in the informal Tripartite Agreement (1936) to its maturity in the Bretton Woods Conference (1944). From Bretton Woods emerged the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and an international currency system pegged to the U.S. dollar. Our first foray into the collection reveals evidence of U.S. action and ties to a historical timeline, laying the path for future research on Morgenthau's role in managing both the policy and the public perceptions of the Roosevelt Administration's ambitions to become the world’s financial engine. (MB)

Our initial phases of work were human analysis. We subjected a set of cards (those indexed under the subject headings ‘Gold,’ ‘Stabilization,’ and ‘Tripartite Agreement’) to an iterative process that included close reading; development of a hypothesis about the emerging patterns; selection, refinement, and expansion of our data set; and progression to transcription and data modeling. Experimenting with machine learning on this selected set of data foreclosed on some of the ways that computer analysis might be used to process data, isolate patterns, and eliminate outliers in a much larger set with more variables. As a sample, our project suggests that the Morgenthau collection data could be mined at a greater depth using both quantitative and qualitative analysis. (MB, JC)

Transcription was an initial stumbling block in creating useful data from the PDFs. The dark, grainy, low quality PDF pages and the occasional misalignment of pages or typewritten characters stymied several OCR readers. Automated transcription could significantly improve over manual entry, especially when working with large datasets. In our case study, one of the three engines offered by OCRspace provided much better results than the other two. The API from OCRspace could further improve speed, and open-source Tesseract should also be considered. The variations in format, however, will always necessitate some manual editing. For image manipulation using an open source photo-editing software, some freeware options are Gimp and Photoscape. (MB)

As a team, we found standardization and classification of the data with keywords necessary, but challenging steps. Team members emphasized different aspects of the data within our own transcription – page numbers; keeping the individual index summaries together regardless if it spanned multiple pages; and breaking up summaries into subsequent rows if a new topic was introduced within said summaries – and provided space for documenting our decisions, developing useful keywords, negotiating, and building our scripting skills and knowledge. We later extracted geographical information to an additional column.

Individually, we tested various tools for data manipulation: OpenRefine, Awesome Table, Google Data Studio, and Orange. Google Data Studio proved to be an open, easily shareable, and beginner-friendly option that we, as data novices could learn quickly. We also found the open source Orange Data Mining tool offers a robust suite of features and convenience; it does not need to be run from a command line and does not require knowledge of Python script. Orange is a more powerful and versatile tool than Google Data Studio and has a steeper learning curve with significant benefits for a sophisticated analyst.

The project demonstrates how mining the cards for keywords and dates can transform static text into dynamic visualizations. Notably, presenting select keywords graphically alongside their dates of mention allows patterns in their use to surface, and showcases how those terms align with pertinent historical dates. One example here is the dramatic shift in terms from ‘Tripartite Agreement’ to ‘[International] Stabilization [Fund]’ after 1940, which signaled that the monetary plan was taking on a broader scope. Visually representing that information presents new avenues for researchers to engage with and interpret the Morgenthau collection. (JC, MB)

Deeper study of this subset of 199 cards could mine the text for geographic information. Our team developed a “place_id” column, which could be used in the future for geospatial visualization, allowing researchers to track major players in the Tripartite Agreement (U.S., Britain, France), as well as those nations considered “junior members” of the agreement, as each entered into the newly developing international monetary system of the 1930s-40s (Morgenthau, 1938, May 9).

Rhetorical analysis and concept mapping could take next steps in highlighting notable concepts related to international economic recovery during the FDR Administration. Taking a closer look at the rhetorical choices made by Morgenthau and other leaders in stabilization efforts during 1933-1944 could potentially reveal additional layers of context and meaning. One example here comes from the “Report on Secretary Morgenthau’s Press Conference” dated October 12, 1936. Morgenthau recognizes that what the U.S. terms “devaluation,” France calls “realignment” (Press Conferences Volume 7 / Book VII, 1936, p. 138-139). “Realignment” suggests a positive take on an otherwise negatively connoted term. What other rhetorical moves might also be documented in the cards and press conferences? Full transcription of the collection as a whole could uncover additional concepts and dates of import, facilitating deeper engagement with primary materials and data visualization possibilities. If transcriptions were embedded into XML documents, TEI encoding could highlight passages related to particular concepts that could in turn be represented visually through topic modeling. (JC)

References¶

- Aldhizer III, G.R. (2017). Visual and text analytics: The next step in forensic auditing and accounting. CPA Journal, 87(6), 30–33.

- Burton, K.D. (2022). “Great responsibilities and new global power.” The National WWII Museum. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/new-global-power-after-world-war-ii-1945

- Chin, M. (2021, September 22). File not found. The Verge. Retrieved August 23, 2022 from https://www.theverge.com/22684730/students-file-folder-directory-structure-education-gen-z

- Donaldson, D.R., & Conway, P. (2015). User conceptions of trustworthiness for digital archival documents. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(12), 2427-2444. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23330

- IMF. (2022). “About the IMF: History: Cooperation and reconstruction (1944-71).” https://www.imf.org/external/about/histcoop.htm

- Morgenthau, H. (1938, May 9). Tripartite Agreement #5. [PDF created from microfilm image of index card original]. Series 1: Morgenthau Press Conference Index, Tax: Legislation (cont.) - Zinc (p. 10), Press Conferences of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., 1933-1945. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY. http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/morg/mp07.pdf

- Morgenthau, H. (1944, April 21). Stabilization #7. [PDF created from microfilm image of index card original]. Series 1: Morgenthau Press Conference Index, Silver (cont.)-Tax: Legislation (p. 147), Press Conferences of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., 1933-1945. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY. http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/morg/mp06.pdf

- Rose, A.M., Rose, J.M., Rotaru, K., Sanderson, K.-A., & Thibodeau, J. C. (2022). Effects of data visualization choices on psychophysiological responses, judgment, and audit quality. Journal of Information Systems, 36(1), 53–79. https://doi.org/10.2308/ISYS-2020-046

- World Bank. (2022). “Bretton Woods and the birth of the World Bank.” World Bank Archives. https://www.worldbank.org/en/archive/history/exhibits/Bretton-Woods-and-the-Birth-of-the-World-Bank